Chris Padilla/Blog

My passion project! Posts spanning music, art, software, books, and more. Equal parts journal, sketchbook, mixtape, dev diary, and commonplace book.

- High-stakes work (giving a performance, recording)

- Busywork (repeating a passage over and over)

- Mental work (arranging and voice leading)

- Physical work (eh, it depends here. I've played music that makes me sweat, but let's just say that the motor skills used are close enough)

- Discovery work (learning new pieces or genres)

- Teamwork (collaboration)

- Creative work (composing)

- The graph entry point is through a triage node. Their example uses an LLM to determine the next steps based on message context. This can be error-prone, but is likely mitigated by the fact that this app uses human-in-the-loop.

- There’s a pattern for recovering from bad calls from the LLM. In this case, there is a

bad_tool_callnode that is responsible for rerouting to thedraft_responsenode in the event that the agent hallucinates a tool. Another point of recovery! - Rewrite Node: Message generation follows two different passes to an LLM. One to write an initial draft (“What do I need to respond with?"), and then a rewrite node. (“What tone do I need to respond with?“) A useful pattern for message refinement.

I Cover the Waterfront Chord Melody

I cover the waterfront,

I'm watching the sea~

Will the one I love be coming back to me?

Arranged by Frank Vignola.

A Patient Pup

My Notetaking Flow

I'm a notes nerd, as should be evident by this blog. Everyone's style is different. Here's mine:

Balancing Physical and Digital

Both have their pros.

Digital notes are searchable, easy to reorganize, tag, group, link back to, and edit. In my case, a huge benefit is that I can actually read what I wrote later. (I have terrible handwriting.)

Physical notes, however, encourage a different kind of writing. It's more free, loose, and sketch-like. Since it's so far away from where a finished essay would land, it feels much more organic. It's easier to get emotions out on a physical page than a text file.

Something about brainstorming is easier on paper as well. I used to be a big fan of huge sketch pads for ideating. Something about moving the arm and laying things out broadly really makes the material feel alive.

I know some people swear by keeping most of their notes and organization in written systems like the Zattelkasten system. The only problem for me is that, compared to digital tools, organizing physical media is cumbersome. I know some people find it therapeutic. But it's not for me, personally.

Balancing Organized and Free Flowing

If your notes aren't a mess, you're doing it wrong. Not everything that you commit to writing should be organized the moment it flows from your fingers. It's highly necessary that a part of your note-taking process be a mess. It simply clogs up creative space if you think about form right from the get-go.

For me, handwriting is great for this. I used to keep a notebook, but then I'd get precious about it. Now, I use printer paper, legal pads, and sticky notes.

It's not important that these notes are organized. They're oftentimes stream of consciousness. Once an idea needs to be cleaned up, then it will move to another system, such as a markdown file or a draft on my blog.

Then, the organization happens. I can tag pages, place documents in specific topic folders, link to other areas, and edit to my heart's content.

I'm taking the time to explain this because, for a long time, I thought note keeping and journaling was supposed to be highly organized from the start. I blame bullet journal Instagram accounts and social media Sketchbook tours of what are essentially portfolio pieces.

Sometimes, I'm able to stay loose in a text editor. It's not a hard and fast rule. The important thing is the spirit of a sketch, digital or physical. (Marshall Vandruff and Stan Prokopenko have a nice long discussion that ends with the same conclusion.)

Whatever your system, if I can give you one takeaway, it's to be sure that you have space to keep things loose.

Full Page Video Across Devices with React

Video on the web takes special consideration. It can be a heavy asset for starters. Due to that, if the video is a stylistic element on the page rather than the main focus, you'll want to have a fallback available while the video loads. And on top of it all, playback behavior may be different between browsers for mobile and desktop environments.

When pulled off, though, they are an attention-grabbing style element. Background videos playing on hero sections of landing pages can set a strong tone right from the start of a user's visit to the site.

Today, I'll share what I've learned while working with my own full-page video project. We'll tackle all the challenges and get a simple 8-second loopable video working across devices.

Accounting for Devices

Before setting up the elements, I want to do some groundwork. I'll need to account for two environments: mobile and desktop. In my case, I want a vertical video playing in a mobile setting and a horizontal video playing on desktop.

To detect this after the component has mounted in React, I can reach for a library to handle getting the window width. Let's go with useHooks/useWindowSize

const FullPageVideo = ({

verticalVideoSrc,

horizontalVideoSrc,

verticalBgImageSrc = '',

horizontalBgImageSrc = '',

}) => {

const isPlaying = useRef(false);

const videoRef = useRef();

const videoRefTwo = useRef();

const pageLoaded = useRef(0);

const [showPlayButton, setShowPlayButton] = useState(true);

const { width } = useWindowSize();

const [mediumSize, setMediumSize] = useState(false);

// . . .

}This isn't necessary, but for my case, I don't need the page to be fully dynamic. I only need the check for window width to happen on page load. So I'm also using a pageLoad count to keep track of rerenders.

I'll then add a useEffect to handle updating the state of the app based on the width.

useEffect(() => {

if (pageLoaded.current < 2) {

if (width > 800) {

setMediumSize(true);

} else {

setMediumSize(false);

}

pageLoaded.current += 1;

}

}, [width]);With that in place, let's get the JSX written for the actual page elements:

return (

<div className="album-story">

<div className="album-story-page">

<div

className="album-story-video-wrapper"

style={{ display: mediumSize ? 'block' : 'none' }}

>

<div

className="album-story-bg-image"

style={{ backgroundImage: `url('${horizontalBgImageSrc}')` }}

/>

<video

preload="none"

loop

muted

type="video/mp4"

playsInline

ref={videoRef}

className="album-story-video"

key={horizontalVideoSrc}

>

<source src={horizontalVideoSrc} type="video/mp4" />

</video>

</div>

<div

className="album-story-video-wrapper"

style={{ display: mediumSize ? 'none' : 'block' }}

>

<div

className="album-story-bg-image"

style={{

backgroundImage: `url('${verticalBgImageSrc}')`,

}}

/>

<video

preload="none"

loop

muted

type="video/mp4"

playsInline

ref={videoRefTwo}

className="album-story-video"

key={verticalVideoSrc}

>

<source src={verticalVideoSrc} type="video/mp4" />

</video>

</div>

<div className="album-story-play-button-container">

<CSSTransition

in={showPlayButton}

timeout={2000}

classNames="fade"

unmountOnExit

>

<button

className="album-story-play"

onClick={onClick}

disabled={isPlaying.current}

>

play

</button>

</CSSTransition>

</div>

</div>

</div>

);Note that I have two video elements on the page: horizontal and vertical.

This seems like it could be a tradeoff. I'm opting to render both elements to the page, but am only hiding them by CSS. Wouldn't this lead to poor performance on page load if I try to download both videos to the browser?

The way around this is pretty simple: Adding preload="nnone" to the video tag will keep the video from automatically loading on the page.

There are tradeoffs there. It means a delay in the playtime of your video. The option starts loading the video once the play button has been pressed.

A more sophisticated solution might be to use a service such as Cloudinary that will dynamically generate your video from the server. Generated videos can be cached and served up quickly. Not a sponsorship for their service, but just a consideration.

In my case, I'll take the tradeoff. The video is only 8 seconds long and loops, so I'm not too concerned about load time.

Fallback Images

Likely, this is not as necessary since I'm not autoloading videos. However, on iOS Safari, I did find that the video image would not show on load. So I needed a fallback image.

This is accomplished with simple overlays in CSS:

.album-story-bg-image {

z-index: -1;

background-size: cover;

background-position: center;

}

.album-story-page {

flex-grow: 1;

flex-basis: 100%;

}

.album-story-video,

.album-story-play-button-container,

.album-story-bg-image {

position: fixed;

left: 50%;

top: 50%;

transform: translate(-50%, -50%);

object-fit: cover;

width: 100%;

height: 100%;

}

.album-story-bg-image {

z-index: -1;

background-size: cover;

background-position: center;

}Playing the Video

There are guardrails in most browsers to prevent autoplaying media when loading a page. Any video or audio is dependent on user interaction to occur first.

There are ways of working around this in certain cases. For video in particular, you may be able to get a video autoplaying if the video is muted. Mozilla has a great deep dive on the subject of handling autoplay scenarios dynamically.

For my case, I'll wait to trigger the video on user click.

const onClick = () => {

if (!isPlaying.current) {

isPlaying.current = true;

song.current.play();

if (videoRef.current && mediumSize) videoRef.current.play();

if (videoRefTwo.current && !mediumSize) videoRefTwo.current.play();

setShowPlayButton(false);

setTimeout(() => setShowTapStory(true), 2000);

} else {

if (videoRef) videoRef.current.pause();

if (videoRefTwo) videoRefTwo.current.pause();

videoRefTwo.current.pause();

isPlaying.current = false;

}

};iOS Considerations

Chrome is my daily driver on desktop. When I went to test this, the behavior was not what I expected.

We already covered the fallback image above.

Additionally, playing the video would literally set it to a full-screen player instead of staying embedded in the web page.

Thankfully, it's as easy as an attribute on the video tag to get this working: playsInline did the trick for me.

<video

preload="none"

loop

muted

type="video/mp4"

playsInline

ref={videoRefTwo}

className="album-story-video"

key={verticalVideoSrc}

>Voilà!

With that, we now have a full-screen video working!

(This is part of an upcoming project on this site. I can't show the results just yet, so I'll share them when it goes live!)

Games as Hard-Work

I just picked up good ol' Wave Race 64 for the first time in years and had a blast. It got me thinking about Jane McGonigal's Reality Is Broken.. Rereading it, I stumbled upon this passage:

What a boost to global net happiness it would be if we could positively activate the minds and bodies of hundreds of millions of people by offering them better hard work. We could offer them challenging, customizable missions and tasks, to do alone or with friends and family, whenever and wherever. We could provide them with vivid, real-time reports on the progress they're making and a clear view of the impact they're having on the world around them.

That's exactly what the games industry is doing today. It's fulfilling our need for better hard work—and helping us choose for ourselves the right work at the right time. So you can forget the old aphorism "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy." All good gameplay is hard work. It's hard work that we enjoy and choose for ourselves. And when we do hard work that we care about, we are priming our minds for happiness.

I'll chime in and say art does a wonderful job of this as well.

Music, for example, checks off several of the different types of "Hard work" McGonigal highlights as present in games:

The timeline for achievement in art, though, is usually loads longer. Games provide an addictively quick feedback loop.

Games also just do a dang good job of making failure fun. More on that later on in the book, but I'll leave it here for now.

All of Me

Why not take all of me?

An Apple A Day

Myst Constraints

Absolutely fascinating hearing the constraints on developing games and software in the early PC era. Linked above is Rand Miller discussing the way Robyn Miller would have to stack rendering 3D images for Myst back to back while he would go grab dinner.

The whole interview is great for more of those nuggets. The memory constraint of CD ROM read speeds is one I hadn't expected.

Amazing that, even with all the resources and speed available to us today, performance constraints remain a top-of-mind consideration for engineers. Albeit, now for optimization, rather than "will this even run at all?"

LangGraph Email Assistant

Harrison Chase with LangChain released a walkthrough of an AI app that handles email triage. For those who have already gotten their hands dirty with the Lang ecosystem, the structure of the graph is most interesting.

On a high level, there's a succinct handling of tool calling. First, A message is drafted in response to an email. From there, a tool may be invoked (find meeting time, mark as read, etc.). Then, the graph can traverse to the appropriate tool.

draft_message seems to be the heavy lifter. Tool calls often return to the draft_message node. Not unlike other software design, a parent component is ultimately responsible for multiple iterations and linking between child components.

A few other observations:

You can find the graph code here. And here is the walkthrough, starting at the explanation of the graph structure.

Oooo~ The Greatest Remaining Hits

Everything about The Cotton Module's future space travel concept album "The Greatest Remaining Hits" is just... cool.

I have to point out, in particular, the domain name: ooo.ghostbows.ooo. You're probably familiar with cheeky uses of country domains. "Chr.is", for example. It's lovely to see a general top-level domain in action (and an onomatopoeia, no less!)

Do treat yourself to the tap essay. It's a delight.

The Essay as Realm

Elisa Gabbert in The Essay as Realm:

I think of an essay as a realm for both the writer and the reader. When I’m working on an essay, I’m entering a loosely defined space. If we borrow Alexander’s terms again, the essay in progress is “the site”: “It is essential to work on the site,” he writes, in A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction; “Work on the site, stay on the site, let the site tell you its secrets.” Just by beginning to think about an essay as such—by forming the intention to write on an idea or theme—I’m opening a portal, I’m creating a site, a realm. It’s a place where all my best thinking can go for a period of time, a place where the thoughts can be collected and arranged for more density of meaning.

Any art is a portal. A painting, a song.

Wonderfully, any creative space is a portal.

The portal of all portals may just be the World Wide Web, where you can create solitary spaces as well as communal ones.

Amiga Lagoon

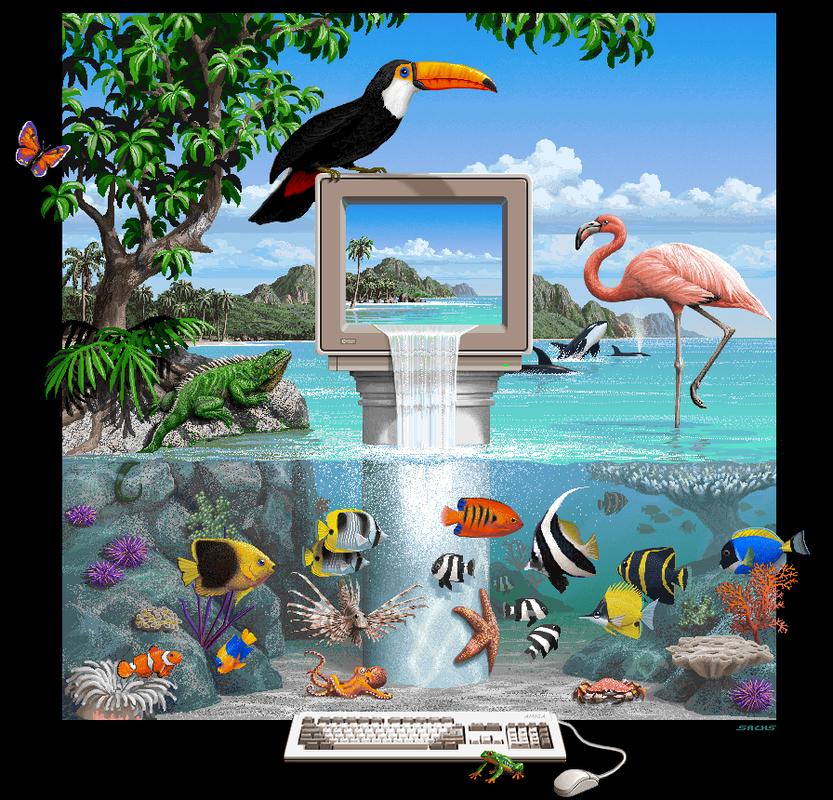

Clint on LGR gave a deep dive on Jim Sach's work with the famouse Marine Aquarium screensaver. What cought my attention is this beatiful predecessory, a cover art piece for the Amiga Brilliance paint program:

More of Jim Sach's art for the Amiga on the Amiga Graphics Archive.

Like Someone In Love

Lately, I find myself out gazing at stars,

Hearing guitars... Like someone in love~

Going Fly Fishing

Finished Work

Robin Sloan makes a case for finished works, even while nurturing a feed:

Sometime I think that, even amidst all these ruptures & renovations, the biggest divide in media exists simply between those who finish things, & those who don’t. The divide exists also, therefore, between the platforms & institutions that support the finishing of things, & those that don’t...

Finishing only means: the work is whole, comprehensible, enjoyable. Its invitation is persistent; permanent. (Again, think of the Green Knight, waiting on the shelf for four hundred years.) Posterity is not guaranteed; it’s not even likely; but with a book, an album, a video game: at least you are TRYING...

Time has the last laugh, as your network performance is washed away by the same flood that produced it.

Finished work remains, stubbornly, because it has edges to defend itself, & a solid, graspable premise with which to recruit its cult.

The ol' Stock & Flow. Can't have one without the other.

In music, it's etudes and jams vs recitals and recordings.

Or perhaps you prefer keeping a sketchbook while working on paintings.

The secret I see working the best for folks is when they can gather up their flow and make stock out of it.